Sunday, September 24, 2006

Viewpoints - Journal

"Today, as part of my working process, it is a given that any actor that I work with must become an expert in working with the Viewpoints. Craft in working with Viewpoints creates instant ensemble. They are the essence of a kind of non-verbal communication and understanding of how I see a performance space and how I expect a performer to be in tune with the space in which he is performing.

Viewpoints are not that mysterious. They are what they say they are. Viewpoints cannot be forced. They already exist in a performance situation by the very nature of our existence in the realm of SPACE and TIME.

The audience experiences them. The actor's life exists inside of them." - Brian Jucha, Director

Click here to read Jucha's whole essay on Viewpoints. Very informative.

http://www.jucha.com/viewpoints.html

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Journal: Read the quote and comment

‘One day I suggested that the students should arrange themselves in a circle - recalling the circus ring - and make us laugh. One after the other, they tumbled, fooled around, tried out puns, each one more fanciful than the one before, but in vain! The result was catastrophic. Our throats dried up, our stomachs tensed, it was becoming tragic. When they realised what a failure it was, they stopped improvising and went back to their seats feeling, frustrated, confused and embarrassed. It was at that point, when they saw their weaknesses, that everyone burst out laughing.’ - Jacque LeCoq, The Moving Body

Thursday, September 07, 2006

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Before Homer Simpson, There Was Commedia Dell'arte

By CHARLES ISHERWOOD

Published: July 22, 2005

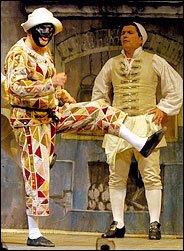

Teenagers attending the Piccolo Teatro di Milano production of "Arlecchino, Servant of Two Masters" at the Lincoln Center Festival should be advised at the start that the fellow in the creepy black mask has not misplaced his chainsaw. He is, in fact, the hapless but resourceful title character, and despite his feistiness, he wouldn't hurt a fly. Instead of chasing nubile young women around with nasty intentions, he will be promoting a more benign form of mayhem, the theatrical delirium that was born a few centuries ago in Italy and called commedia dell'arte.

The small explosions of giggles that burst like firecrackers during a recent performance of this comedy by Carlo Goldoni, at Alice Tully Hall through tomorrow, attest to the durable nature of this much referenced but little seen theatrical style. As Arlecchino digs himself deeper into trouble, and gets himself out of it without a scratch, it's easy to forget the period costumes and the masks and take an irony-free, childlike pleasure in comic archetypes whose influence cannot be overstated, stretching as they do from Shakespeare to Homer Simpson.

Technically, commedia dell'arte was on the wane by the middle of the 18th century, 200 years after it sprang from the streets. Goldoni's play, first written in 1745 and revised thereafter, uses the characters and conventions of the genre, preserving its essence, while codifying it in a way that naturally changed it. Traditionally, the form drew heavily on improvisation and the particular gifts of the actors who established careers playing its stock characters: the bumbling servants, Arlecchino and Brighella, and their pompous and foolish superiors, Pantalone and Dottore.

Fast-forward two centuries. Enter Giorgio Strehler, the visionary Italian stage director and founder of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano. In presenting "Arlecchino" as the last attraction of the company's opening season in 1947, Strehler sought to revivify a by now well-known text by returning it to its roots, stripping down the dialogue to allow for more free-form interpolations by his actors. The revised production became a mainstay of the company's repertory, restaged regularly and seen in more than 40 countries and at more than 2,000 performances, according to a glossy souvenir program printed for the current American tour. (The production will be seen in Colorado Springs next Friday and Saturday, and in Los Angeles; Berkeley, Calif.; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Minneapolis; and Chicago in the fall.)

Strehler's "Arlecchino" has even survived the man himself, who died in 1997. The production at Lincoln Center has been restaged by Ferruccio Soleri, who has played the title role for more than four decades and undertakes it again here.

This long and estimable history - lesson concluded, by the way - and the production's stature as an ambassador for Italian culture across the decades would seem to suggest that audiences are in for an evening of great cultural significance. Fat chance. Yes, theater historians can note the ways in which the production hews to tradition, including the use of masks for the comic male characters and the presence of an actual slapstick - two pieces of wood that are struck together for the sound or comic effect. It also uses a by now familiar meta-theatrical frame: Ezio Frigerio's set, recreating the feel of an old village square, allows us to watch the actors chat and idle when they jump off the cramped wooden platform that supplies the playing space.

But anyone who has seen a Saturday morning television cartoon, an Abbott and Costello movie or a sex farce will recognize the comic techniques here. Commedia dell'arte simply mines humor from human folly by exaggerating behavior and manipulating language, and that recipe has never gone out of style.

Happily, Mr. Soleri's restaging of Strehler's production doesn't evince signs of fatigue, either. As an actor, Mr. Soleri, now 75 - well past the age of advanced acrobatics, you would think - must be an inspiration to his colleagues. His nimble performance as a servant who sows confusion when he takes on two employers is a continual delight. A set piece in which the starved Arlecchino makes a meal of a fly raised peals of joyous disgust from the children in the audience. And the gymnastic scene in which Arlecchino sprints back and forth to serve his masters their dinners simultaneously is a marvel of cleanly choreographed farce and a fine feat of juggling, too.

The rest of the cast is also adept at embellishing the stock situations of the plot with inventive use of absurd but articulate physical or vocal mannerisms. Paolo Calabresi, as Dr. Lombardi, the outraged father of a rejected suitor, turns his mountainous stomach into a glorious prop, a perfect foil for Giorgio Bongiovanni's skinny, wheedling Pantalone, the father of the young woman whose affections are at stake. In this role, Sara Zoia simpers and preens effectively, demure and hysterical by turns.

The play is performed in Italian, with English supertitles, an unfortunate necessity. Audiences who don't understand Italian may get more pleasure by consulting the program's synopsis before each act begins, to focus on the actors as much as possible. Or maybe ignore the supertitles for one of the play's three acts: the second one, with its long stretches of pure physical comedy, would be a natural choice.

Adding some kind of variety to the evening is probably a good idea. At three full hours, with two intermissions, this is a very generous immersion in pure buffoonery, even if it is the kind of buffoonery that inspired the term. Strehler's "Arlecchino" may be hallowed by years of acclaim, but the actual experience of watching it could be compared to sitting through a three-hour director's cut of a Hollywood comedy rated PG-13.

Modern Clowns With a Fear Factor - NYTimes

September 3, 2006

THEATER; Red-Nosed Life Lessons: Clowns With a Fear Factor

By STEVEN MCELROY

Just as a tiny car at the circus might let out a seemingly endless succession of oversize shoes and red noses, New York's out-of-the-way theater scene seems to be overflowing with clowns.

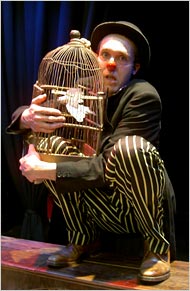

Besides two entries in the recent New York International Fringe Festival, a new clown and variety showcase started last month at 3LD Art & Technology Center in Lower Manhattan, ''Creation: A Clown Show'' is running through next Sunday in Midtown, and the New York Clown Theater Festival opened this weekend at the Brick Theater in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. These are not birthday party pranksters, either, but fools, buffoons and harlequins who are serious, trained performers.

In the opening moments of ''Creation,'' for instance, Lucas Caleb Rooney walks onto the stage, notices a room full of people staring at him and screams in fear as he desperately (and unsuccessfully) tries to escape. The effect is immediate and powerful: the audience, unexpectedly in control, experiences a grand moment of schadenfreude and laughs at his apparent terror.

''It's ultimately what we go to the theater for,'' Mr. Rooney said in an interview. ''The person who is going to take their heart out and let you touch it.''

Fear may be the common denominator among the new generation of clowns. It does seem inextricably bound with clowning. For starters, many people profess to have coulrophobia, the fear of clowns. And like Mr. Rooney, several of the new clowns have made their own fears an integral part of the performance.

''We live in a time of enormous cynicism and we live in a world that is boxed in,'' he said. ''The clown says we're all freaking out and we're all the same under the clown exterior.''

Eric Davis, who is presenting two shows at the Brick this month, parses it even further: ''I think the exciting pieces in the movement are dealing with the very complex nature of being not just human, but an adult. They're visual and funny, but they're also philosophically challenging and intellectually provocative.''

Mr. Davis recently appeared in yet another new clown show: the New York Downtown Clown Monthly Revue. For the past four months, in a hot basement on St. Marks Place in the East Village, the revue has drawn a capacity crowd for characters like the Candidatos, Little Brooklyn and the Great Grazini and Coccina. The host, Christopher Lueck, who is also a producer of the event with Amanda Pekoe, is a clown himself and recently presented the solo ''I Want to Be Musashi: A Clown Samurai Fantasy,'' at the Fringe.

''There is a feeling that we're all very excited because it feels different and new right now,'' Mr. Lueck said. ''The really great clowns are getting older, and a lot of our role models are not performing as much anymore. So we feel a need to perform.''

Clowning has probably not been so prominent in New York theater since ''Fool Moon,'' starring Bill Irwin and David Shiner, was on Broadway in the 90's. Mr. Shiner, who also teaches clowning workshops worldwide and will run one at the festival, said he had seen an increase in students in the last decade. ''I think it's slowly been building,'' he said by phone from his home outside Bavaria, ''but it's not happening as fast as I would like it to happen.'' He pointed to a long tradition of clowns as part of the fabric of American entertainment. ''When you look back to the greats like Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy, there is something timeless about that they did,'' he said. ''There is great artistry that has been lost.''

Another well known teacher, Christopher Bayes, and several other clowns noted that more graduate acting programs were offering classes in clowning and physical theater than they did just a few years ago. ''We have been ensconced in a playwright-centered form for so long that I think it can be refreshing to find the actor at the creative center once again,'' said Mr. Bayes, who has taught at Yale, New York University, Julliard and Brown. ''Many actors out there have been inspired by the work and the possibility of actor-created theater.'' For the audience the appeal stems from the vulnerability of the actor. Despite the humor and goofy outfits, the actual performance is often moving, even sad. ''When you look at the clown, you understand,'' Mr. Bayes said. ''He's like a skinless grape.''

Or as Anna Zastrow put it, ''The essence of clowning is that people can recognize themsxelves in the clown.'' In a sequence in her show at the Fringe she is waiting for a very important and potentially exciting call. A date? A job? When the phone rings, finally, she freezes up. ''My clown is a reflection of a person kind of overwhelmed by life and wanting so much to be part of it,'' she said.

But ultimately we're talking about a bunch of clowns. ''There's something about someone falling on their face that will always be funny,'' Mr. Shiner said. ''We all know what it feels like to be an idiot.''